My WWII Service on LST 655

As told to Paul Benton

Don Wolfe upon his entry into V-12 Program, July 1, 1943

We had some excitement the first night we entered the Mediterranean. Late that night, we heard general quarters sound, so we all went to our battle stations. There were German aircraft overhead. The whole convoy was told not to fire until we could see what was developing. Then all of a sudden, on one of the ships, someone started firing …

— Don Wolfe

Don as a baby

Where it All Began

My name is Don Wolfe. Homer is actually my first name, as it was my father’s. I am a native Californian; I was born in San Diego in 1923. I had an older half-brother on my mother’s side, as my parents had both been married before. His name was Vernon West and he was about 14 years older than I.

His nickname was Bud, and everyone called him that.

I lived in San Diego for about 10 years, and then the Depression of the 1920s and early 30s finally prompted us to hit the road.

My dad was looking for work, so we moved a lot, and I went to a lot of different schools in a few years.

My mom had a sister who lived in Long Beach and another in Monterey, so Mother and I spent most of our time living with one aunt or the other. It all played out and seemed like a long time in my life, but the thing that bothered me the most was changing schools.

I went to school in Long Beach shortly after they had an earthquake there (1933). The schools were quickly rebuilt using a simple construction technique, wood up so far and then canvas on the top.

Don as a young boy

Finally, in 1934, when I was 11, we settled in Modesto, CA and lived there until I went into the service in 1943. I never lived there again after that.

My dad’s brother had gone there and they were in the same kind of business, shoe repair, so he started working with his brother, and eventually we made our home there. I was 11 years old when I started Junior High, went to school through Modesto High, and then on to Modesto Junior College. From there I went to San Jose State. I was majoring in social science – my plan was to be a teacher and a coach, and I did eventually achieve both those goals.

Don in uniform

A Navy Man

In my junior year at San Jose State, 1943, representatives of the different services came by and presented their programs to the civilians who were still there. I opted for the Navy, as their program sounded good to me. The Navy guys turned out to be the only ones who got to finish their entire school year, which was their junior year. The program that I got into was called “V-12”.

The program was such that if you had finished three years of college, you were entitled to one semester in V-12. The V-12 units were established at over 200 hundred colleges and universities. You were required to take the courses designed by the Navy, such as math, physics, and engineering drawing. If you could work it in, you could take courses in your major or minor.

Beginning July 1, 1943, I got my first orders from the Navy, and was surprised – I was going to North Dakota! That was a little strange to me, as I had joined the Navy and was now being sent to the geographical center of North America. I spent one semester there at Valley City Teachers College in Valley City, North Dakota. Then I was transferred to the midshipman’s school at Columbia University in New York City.

It was a four-month program that included seamanship, navigation, and all those kinds of things. I wondered, as the time for graduation neared, if you had to be 21 to be a commissioned officer, as I was only 20, but I turned 21 shortly after I graduated. I guess it didn’t make any difference as long as you could pass the program.

I had my first official assignment. I was assigned to New Orleans, because there were a lot of newly built ships that were coming down the Mississippi River, and those were the ships to which we would eventually be assigned to. Most of those ships were LSTs, Landing Ship Tank.

A picture of the LST Don was assigned to, Number 655. The photo was taken as it was launched. He was aboard for 27 months.

In Awe of the LST

When we left midshipman’s school in New York, I hadn’t realized it, but we were being shipped out in twos, and so I latched up with another guy from the midshipman class, and together we were assigned to the “655”. His name was Masil Danford. We did everything in New Orleans together, and became close friends

Meanwhile, LSTs were being built in large numbers, and this is the unique thing about my story – I was sort of in awe of the ship that we were on. It was a unique vessel.

It was designed so that it could run up on the beach, the bow doors could open and a ramp could come down, and the tanks, trucks and whatever could go ashore. Running that thing onto the beach called for another unique feature, and that was a stern anchor. Before we started into the beach, at a certain point you would drop the stern anchor and let out the cable. When you got ready to retract from the beach, the engines would go into reverse, and the anchor cable was used to pull us off of the beach.

The LST was actually an idea of Winston Churchill’s. This was because of the Dunkirk experience in 1939 along the coast of Northern France. The French and British troops had no way to escape, so they used fishing boats and anything that floated to get them off of the beach. They lost quite a few people that way. Churchill’s idea was they should build a ship that could go right onto the beach in places that did not have normal docking facilities. The LSTs were it. They were used all over the world, in the Pacific and the European theaters. Altogether about 1,500 of them were built in the early 1940s.

We trained for whatever the assignments were. I became an Assistant First Lieutenant.

I didn’t even know they had a “First Lieutenant” in the Navy, but it wasn’t actually a rank, it was a position. I found out that the First Lieutenant was responsible for the upkeep of the ship, being in charge of the crew for unloading and loading the ship as needed, and being a good housekeeper. I was his assistant. Later on, after the invasion of Southern France, the Captain got orders to transfer two officers. Danford and I figured we were it since we had come together, but they transferred two other officers instead. So Danford became the Communications Officer and I became the Gunnery Officer.

Some of my duties included taking the gunners mates to different training sessions, and holding drills, to prepare for emergency general quarters. Everybody had a position and a place they had to be when we went to general quarters. We provided onboard ship training for the whole crew.

A lot of the LSTs were built in what they called the “cornfield shipyards.” These were mainly along the Ohio and Illinois Rivers, and after being launched, they were transported down the Mississippi River to New Orleans, where they had the masts attached. Coming down the river they had bridges to go under, so the masts were not attached until they reached New Orleans. So our ship got ready to go down the rest of the Mississippi into the Gulf of Mexico, and carry out what they called a “shakedown cruise.” We floated down the Mississippi, practicing all of the things we had to learn how to do. There were no problems, and it worked out pretty well in all cases.

Back when I was in midshipman’s school, and before we graduated, they had asked us what kind of assignment we wanted. We all knew we were going to “amphibs” somehow, so I requested an LST, because that was the largest of the bunch. I had been hoping for an assignment to the Pacific, but I got the Atlantic instead.

First Excitement

After New Orleans, we headed up the East Coast, continuing our exercises and for further outfitting of the ship, before heading across the North Atlantic. We left the East Coast in June, 1944, when the Normandy invasion was one week old. We traveled in a convoy with other LSTs and escort vessels.

We had some excitement the first night we entered the Mediterranean. Late that night, we heard general quarters sound, so we all went to our battle stations. There were German aircraft overhead.

The whole convoy was told not to fire until we could see what was developing. Then all of the sudden, on one of the ships, someone started firing, and pretty soon they all were firing, in different directions. We found out later that three German fighter planes, dive-bomber types, had gone over the convoy. We didn’t hit any of them and there was no damage done either way.

We continued on, and eventually docked in Bizerte, Tunisia. We spent a bit of time in and around that area, then went back to sea again, and on to Salerno, Italy. We then got ready to go to the South of France.

I have read since that the timing of the Normandy Invasion and the invasion of Southern France were originally planned to be on the same day, but supplies, ships, men and everything couldn’t be assembled fast enough to stage them both simultaneously. So the invasion of Southern France took place about two months later.

The Invasion

When we got our orders to go to the South of France, I wasn’t apprehensive, for some reason. As 21-year-olds, we did what we had to do. One item of interest is that, while we were gathering and getting ready to leave Naples, Italy, one of the officers came down and said, “Hey, I just saw Churchill out there!” I tried to look over to see him, but his motor launch had gone. He had come to send off the troops that were going to Southern France, with his famous V for Victory sign.

I heard he was actually opposed to the Southern France invasion – there were a lot of politics involved. He felt that an invasion up around Trieste, on the eastern side of Italy, would have been a better plan, because he felt Stalin was going to be a problem later on, and he wanted to deal with him early on by occupying the Balkans.

Eisenhower, however, was in favor of the Southern France landings, so that is what we did. The original idea was that these troops coming in from the south of France would head north and meet up with those from Normandy. The invasion of Southern France was code named “Anvil.”

On the way to the landing beaches, the Army guys had most of their equipment stored on the tank deck and their smaller trucks were carried on the main deck. These smaller trucks were armed and had a two man crew assigned to each truck. Since we were at general quarters during the entire trip, those Army guns were also manned. The day before we got to the point of the invasion, we heard gunfire – one of the Army guys had leaned against his gun in such a way that it had gone off, and he had blown the back out of one of our small boats.

Our ship originally had six racks of small boats. They were called LCVPs, Landing Craft Vehicle Personnel, and were the boats that the 45th Infantry Division guys were to get to shore in. So here we were with this boat that we had to use the next day, with its back end blown out. Fortunately, we had a guy on board who was a shipfitter, and we also had a ping pong table that belonged to the crew.

He made a new back for the boat out of the ping pong table, got it all repainted the official gray and blue, and it was used in the invasion the next day. We got up to the coast of France, and all six small boats were ready to go in with the first wave of infantry, at eight o’clock in the morning. Our army personnel went ashore, and on the way in we had our only casualty – one of the Coxswains in the small boats was shot in the shoulder.

The officer in charge decided to go about their business, made the landing, and then went back to the ship to get the ship’s doctor. It turned out that he was a pediatrician. We said, that always worked well, we were a young crew anyway. After the invasion, the wounded man was taken south to Ajaccio, Corsica, where he was hospitalized, and then later he rejoined the crew.

Top Secret

I have a map that shows the plans to invade Southern France. At the time it was labeled “Top Secret,” but it is OK to look at it now.

Our ship was sent to beach number “263B.” There were three beaches in the cove in question. There was also a German gun emplacement on the west side. As a consequence, the officer in charge of our small boats later told us that the boats from the other ships who were supposed to be heading for beach 263A – the western part of the cove – kept crowding towards the other boats on the right to keep out of range of the German guns.

The closest town to the landing beach was San Maxine. After the war, I had a friend who was going there to visit one summer, so I made him a copy of the invasion map. He took it to the library in San Maxine, and they had a map just like it on the wall, except they only had one side of it. So he gave them his copy, so they would have both parts. Several years after the war, I went back to that beach and looked for the gun emplacement, and it was still there!

I never went onto the beach during the landings. My job that day was to coordinate the opening of the bow doors and the dropping of the ramp, because that has to take place just as you are approaching the beach. I was positioned up underneath one of the forward gun tubs, and was in communication with the Captain, and would tell him when to give the orders to open the doors and lower the ramp. The operation went very smoothly.

There were a lot of other vessels and LSTs at the invasion. There were also a lot of things the Air Force had done to make it more of a surprise for the Germans. For example, they had dropped dummy paratroopers further to the west of where we landed to draw the Germans to that location.

Those things seemed to have worked OK, because we went in without much opposition. Most of the problems occurred to the east of the bay we landed in – we lost one LST over there.

In the last few years I have become acquainted by telephone with a crew member from another LST near the ship that was lost. He was a quartermaster on his ship, and later wrote a book titled “Defeat and Triumph.” The book was extremely well researched, and was a very complete story of the Southern France Invasion.

I am a member of the National LST Association; they have a newsletter that comes out every month, which is where I saw his book mentioned, along with his phone number. So I called him, and we talked at different times, exchanging stories and memories.

The reason that his book is called “Defeat and Triumph” is because that was the time when France regained its sovereignty as a nation. It took this invasion to achieve full sovereignty.

The thing that bothered me most about the whole landing was that there were battleships out there behind us, and they were firing over our heads into targets on the shore. I felt a little uneasy about that!

Shortly after the landings we moved the ship out, and went into Ajaccio, Corsica, where we waited for further orders. We made several additional trips back to the south of France with troops and supplies.

One of our stops was in Nice. While we were in port, a terrific storm came up, and the ship was bouncing around like nobody’s business. It was tied up at the dock, and one of the coxswains in a small boat equipped with fenders used it to keep us under some control.

But it got so bad that the captain decided that we would get under way and ride out the storm on the open sea. It was a strange circumstance, because you don’t usually take a Navy ship or vessel like that to sea without orders.

Anyway, he took the ship down to Naples, and some officer who was on shore duty there said, “If your captain had brought his ship in here, he would have been court-martialed.” But as it turned out, other LSTs had been destroyed in that storm. So the Captain was given a commendation instead.

The 655 at anchor in Lake Bizerte

Crossing the Atlantic

I never got seasick, but I got “sick of the sea” when we came back across the Atlantic. It was January 1945. There weren’t a lot of other LSTs in the water because they are flat-bottomed, and the ocean was very rough. It took us three weeks to get home, up and down all the way. I have a few pictures some of the guys took, and you can’t see anything – the swells were so big. That’s why I got sick of the sea. Your body is moving all of the time and it is just tiring.

To pass the time, I remember the Executive Officer taught all the officers how to play bridge. He would walk around the table and see all our hands and would say, “You can beat ’em”. He was the Major Domo. There were times when we had movies on board, and we had a basketball backboard on the tank deck. The Captain OK’d it and we used to play basketball there as often as conditions permitted. It just kind of amazes me now.

Most of the officers who went on duty while under way usually took a cup of coffee with them. I was not a coffee drinker so I took some bouillon cubes and a cup of hot water so I could be reasonably warm on duty at night. We were “station keeping,” which is maintaining the proper distance from the ship in front of you when traveling in a convoy. During this trip it was so rough; we didn’t have any sit-down meals because you couldn’t keep any food on the table. So we ate sandwiches all the time.

When we got back to the East Coast, there were new assignments for most of the officers. I became the navigator. Up to then, the navigation had been done by the Executive Officer. He became the sole Executive Officer and I became the Navigation Officer. I’d had some instruction in navigation in midshipman’s school, but he gave me a few pointers and it all worked out fine. We got there and we got back, albeit with a few course corrections along the way.

When we got back to the United States there were officers on board who were going to be transferred. They remained on the ship in dry dock in New Jersey, while the rest of us went on a 30-day shore leave. When we returned we resumed our regular job on the 655.

One of the guys was going to Chicago by train to see his girlfriend. I was planning on flying out of New York to San Francisco, but he convinced me that I should go with him by train. I did that, and then tried to get an air transport plane out of Chicago. I got a flight out, but it only went as far as Kansas. So I ended up in Kansas, and from there I got another flight out to San Francisco. So that is how I spent my 30-day leave, nothing special.

I do remember one incident, however. I went out to the junior college gym in Modesto. The floor was dirty, and I slipped and tore the ligaments in my knee. Fortunately, there was a Navy facility west of Modesto, where my cousin took me to get treatment. They took good care of me and patched me up.

Soon the 30-day leave was up and we were back in New York. Then, back to the ship, which was in dry dock, and to several personnel changes, with some enlisted men assigned and several officers reassigned.

On to the Pacific

Following new orders, we headed out, went south and dropped a guy off at Guantanamo Bay. After that, we went farther west and on through the Panama Canal. It was my first time going through the canal and it was an exciting experience. We then headed up towards San Diego. At that point, we got the message that President Roosevelt had died. We were befuddled by the news and asked, “Who is Truman?”

I remembered back to when we were over in North Africa – they had had absentee ballots for overseas servicemen so they could vote in the 1944 Presidential election.

I was 21, and I had cast my first vote for Roosevelt, for his unprecedented fourth term.

We eventually reached San Diego, my hometown. I had the opportunity to go ashore and visit my many cousins who still lived there. Then we set off for Hawaii. It was a brief but pleasant trip. It was several years after Pearl Harbor when we arrived in Honolulu, and still a little depressing to see the sunken ships.

A funny thing happened after the war, after I retired. I started taking courses in travel and tourism, and on one of those trips, called FAM trips, or familiarization trips for travel agents, I sat next to an Asian woman from San Jose, who was of Japanese descent. She told me she had lived in Hawaii in 1941, and that on the day of the attack, they thought it was just a training exercise, because there was so much of that going on at that time. It took them a while to realize it was the real thing.

The ship’s itinerary from Pearl Harbor then took us out farther into the Pacific, to Guam. We checked in there and were given further orders to go northward to Saipan in the Marianas. That was kind of an interesting stop, because Saipan was where the Japanese had been hiding out in the caves and the hills.

Next to Saipan was the island of Tinian. The thing that intrigued me most about Tinian was that it was a complete flat-top – a 24-hour-a-day airfield. Every night I would watch planes take off and fly north and west.

Our orders then took us to Okinawa. We had a Seabee unit on board that we had picked up in Pearl Harbor, and we discharged them there. Just after we got there, an air raid woke us all – the kamikazes were very active in that area.

We were moored on the east shore of Okinawa, but we were not in that location very long when we got orders to go back out into the bay, and another LST took our place. Just a matter of hours later, that ship was destroyed by a kamikaze.

There is a small island near Okinawa called Ie Shima. That is the island on which (there are pictures on page 143 of the book I later wrote) Japanese Bettys (aircraft), with a team of Japanese envoys, landed in 1945, on their way to meet with General MacArthur in the Philippines to discuss surrender.

The unique thing about the photos is that after the war, I couldn’t remember where I got them, but I found out later they were taken by my future wife’s brother, Hibbard Moore. At the time, I didn’t know that, as I hadn’t even met his sister yet.

Hibbard was a photographer as well as a pilot during the war, and was on Ie Shima at the same time I was. I ran across these pictures many years later, and included them in my book. Later on, I gave him a copy of the book, and he told me he had taken the pictures.

One time, he and his wife were traveling up in Oregon. She was grocery shopping and he was looking through a magazine, and those pictures appeared in that magazine. He recalled that his commanding officer had taken the film from him and was going to turn it over to his commanding officer, but never knew what had happened to it after that.

Prisoners of War

We stayed in and around Okinawa for a while, then we were sent down to the Philippines. That was quite uneventful, although there is one incident I recall.

We always traveled in a convoy and not by ourselves. We were headed north to Okinawa at the time, and we got orders to go back to the Philippines because there was a typhoon headed towards Okinawa. On the way back, we spotted something in the water. It was a group of five or six Japanese guys who had been hiding out in the Philippines, and had gotten a hold of a boat somehow and were headed back to Japan. One of the escort vessels took them on board as prisoners of war, and we took their small boat in tow.

I think we probably saved their lives, as they would have never made it in that typhoon. We turned them over to the Army, and got headed back north again when it all subsided.

After the war had ended, we were given a unique assignment. The Japanese had been slowly infiltrating the northern part of China (Manchuria) for years. We were assigned to make a trip to China to pick up Japanese civilians and evacuate them. This repatriation trip was interesting. The civilians came on board with their tatami mats, and slept on the deck, a metal deck! Unfortunately, during the night, one of the women rolled over on her child, and it died. So we held a burial at sea.

Don and Marian on their wedding day

The War Ends

After the war ended, it was a strange time. We started getting messages, including orders for Danford and me. Our orders were to depart the 655. They named a replacement for me, and Danford was to report to the US immediately. But it was three or four months before my replacement caught up with the ship, and I had to wait. He finally caught up with the 655. That was in Tsingtao, China.

I then had to make arrangements to get home from China. I moved to a floating hotel in Tsingtao, and waited. About two days later, a cruiser came into the harbor. They said I could get on board, but it remained at anchor for about a week before it finally left for the US.

Eventually, I got back to the Los Angeles area and called my brother, who was already out of the Navy. He lived all of the way out in El Centro, but his wife told me he was in Los Angeles, on an assignment for a store he worked for. So I looked him up, and spent the night with him. The next day I got the bus to Modesto. I had called ahead and told my folks I was coming home, so it wasn’t a surprise. But I wasn’t discharged from the Navy yet, and I got another weird assignment. At that time they were putting a lot of ships in mothballs.

I got an assignment to the Navy Yard at Hunter’s Point, as a hull inspector on the LSTs. It was kind of a thankless job, looking at these ships that were in dry dock. Well, that didn’t last very long – I was given the assignment to report as the commanding officer of another LST. I reported for duty, but it turned out that someone else had already beat me to it, so they assigned me to another ship.

My job was to take that ship up the coast, to Portland, Oregon, for its final voyage. That was LST 1079. I took it up to the Columbia River, got a river pilot, and then returned to San Francisco to be discharged from the service. It was 1946. You’re with so many people for so long, and then all of a sudden you are all by yourself. You are free to go. That was in the spring, and I went back to Modesto.

Don and Marian with daughters Patricia (left), Cathleen (center) and Deborah

Return to Civilian Life

I had left college at the end of my junior year in 1944, gone into the V-12 program, and three years later, I was re-entering San Jose State. That is where I met my wife, Marian, in a sociology class. She was a senior, and graduated with a double major: Occupational Therapy and Music. We were able to graduate together in 1947.

She had to take the national exam for certification in occupational therapy, and I had to do my student teaching to complete the requirements for my teaching credential. With those items taken care of (and with a job lined up), we were married in July, 1947.

My job was to be at Washington Union High School in Centerville (later incorporated as Fremont, CA) and I was to teach social studies and coach baseball. That couldn’t have been a better combination for me. I had been a Social Science major and a P.E. minor at San Jose State and had played basketball in high school, junior college, and college.

Marian had been asked by the head of the Occupational Therapy department at San Jose State if she would accept a part-time job with their department. We felt very fortunate to be starting our married life with employment and in fields that appealed to us both.

As it has turned out, we lived in Fremont for 46 years before moving to the Mother Lode in 1994. Marian worked for just a few years before we started raising our family. We have three daughters: Cathleen, who lives in Massachusetts, Patricia, who lives in Tuolumne, and Deborah, who lives in San Diego. We also have lots of grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

As for me, I spent 35 years in education in Fremont – 20 of those years in the high schools teaching and administration; the last 15 years at Ohlone College, a community college which opened in Fremont in 1967. There I worked as an administrator in Student Services. I enjoyed it all!

Don Wolfe at home, March 2014

Becoming an Author

About 12 years ago, I wrote and self-published a book about LST 655. The name of the book is “USS LST 655, A Ship’s History, 1944-1946.” There is a copy in the local library. On page 57 there is a picture of our ship, combat loaded, taken just before we headed up for the invasion of Southern France.

A few years after the war ended, we started having ship reunions. At the reunions, someone was always talking about doing a history, but it wasn’t getting done. I thought, gee, I wrote enough term papers as a social science major, I should be able to do this. So I found out I could get copies of our ship’s daily logs from the National Archives, which gave me a firm foundation and timeline for the book.

I wrote to the guys I had seen at reunions, told them what I was doing, and asked them to send me their stories and pictures, and so forth, and I put them all together. That was in 2002.

When I started on it I had no idea it would turn out to be a real book. I thought it would just be a small booklet of some sort. It just got out of hand!

In Summary

The scariest experience I had during the war was the southern France invasion. Bombardments were going overhead as the landing craft were going in.

The thing I learned most from my wartime experience was that I was part of a team, and everyone had to do their part to contribute to the success of the team. I am also more organized than I might have been otherwise. It paid off in the administrative jobs I had.

Don’s book

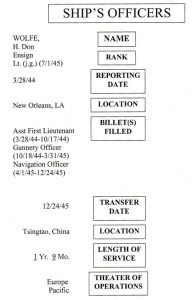

Don Wolfe’s dates of service and assignments