As told to Chace Anderson

Steve Klesitz at 18 just before he was drafted. He carried this photo for the entire nine years he was held captive

A Long Time Ago

When I was finally released from Tiszalok prison camp at the end of 1953, I was 27 years old and had spent one-third of my life as a World War II POW.

For more than five and a half years I was held in a series of prison camps in Siberia, and for three more, the post-war communist regime in Hungary imprisoned me as part of a slave labor force in my home country. You must wonder how all this could happen.

The Beginning

My parents had a little farm in the small German-speaking town of Bakonysarkany in Hungary. I was born Stefan Klesitz in June 1926, and had an older brother, Joe, and a younger sister, Regina.

Our farm was very simple. We had a couple of cows, two horses for plowing, and a pig, and we raised corn and a little potatoes. Sometimes there was extra to sell, but most of what we raised supported our family. Of course no electricity; the lights ran on petrol.

The Klesitz family in early 1930s;

Steve is on the left in front

The town was small, maybe 1,000 residents, and everyone spoke German. In school we learned Hungarian, but I hated school. It was run by the Catholics, and they had a terrible philosophy. If you were late, they beat you. If you didn’t know an answer, they beat you. If you laughed in class, they beat you. They had a bamboo stick, and even in summer when we wore shorts, they would swat you on the back of your bare legs.

Every week you had to go to confession, and I would make something up to confess just to get it over with. The minute I got away from my hometown, I never went to church again.

War

I was about 13 when the war broke out in Europe, but we didn’t feel it too much in my hometown. At the beginning, Hungary was not attacked or occupied by Germany, but the Hungarian leaders allowed Hitler to travel through Hungary to Russia.

In 1942 the war was still going pretty well for Germany, and my brother Joe volunteered to become a member of the Waffen SS. About that time my father died of cancer, and I quit school to stay home and run the farm.

After the Battle of Stalingrad went so bad, things changed for Germany. In 1944 Hitler decided to occupy Hungary, and by then Germany was drafting men from about age 17 all the way to about 42. There were no more volunteers. Even the Waffen SS started drafting soldiers, and that is what happened to me in September of 1944 shortly after I turned 18.

They were taking everybody by then. Even a school buddy who had severely broken his leg and ended up with a knee that wouldn’t work was told he’d be perfect for kitchen duty.

I became part of the 22nd SS Cavalry Division, Maria Theresa, and was sent to a nearby town for training. That late in the war, the Romanians had thrown in the towel and were fighting with the Russians, moving quickly into Hungary. Troops were needed in a hurry, so we only had one month of training before we were sent to fight.

Like other members of the Waffen SS, we had our blood type tattooed on the inside of our left bicep. Originally, the Waffen were the most valued of the German military branches and were thought to be the most worthy of medical care if wounded. During triage the tattoo would notify medical personnel which soldiers were SS.

By 1944 the Waffen was no longer purely volunteer, but the practice remained, and conscripts like me were still tattooed. The little “A” on my left arm would eventually cause me a lot more trouble.

I didn’t know what the hell I wanted to do in the army, but I knew I didn’t want to walk. My buddy and I saw some BMW motorcycles where we were drilling and decided that is what we wanted, so we volunteered for reconnaissance.

In October the Maria Theresa division was sent out to the Hungarian flatlands and stationed in a little place called Kecskemet. The Russians were already in the area, so those of us in reconnaissance would ride out on our motorcycles to try to gather whatever information we could.

By early November the weather was rotten, really rotten, and there was no reconnaissance, just lots of rain and lots of snow. We lived in the trenches then, and you had to be careful. You’d stick your head up and maybe get shot.

I had a MG42, the fastest machine gun in the war, and I would fire anytime there was an attack. Did I ever hit any of the Russians? You didn’t really follow the bullets, but I must have killed some of them.

By the middle of November, nobody really knew where the front lines were. The Russians were trying to surround Budapest, so we did more reconnaissance.

On Christmas Day, they called the whole division back to a town called Soroksar, and we had a little ceremony at a school where they gave out medals and decorations. I hadn’t been in long enough to earn anything, and I wasn’t that brave.

Wounded

We marched all that night out to Vecses where the airport is now. The next day, December 26, another machine gunner and I were ordered to set up our guns and guard a bunker about 50 meters away where officers were meeting. We had two machine guns, one that was pretty new and an older one that always seemed to jam.

The other guy and I took turns going to breakfast. He went first, and when he came back, I started to go. But at the same time an officer yelled, “Everybody out! The Russians are coming!”

I grabbed the old machine gun and started monkeying with it to make sure it wouldn’t jam. Then I heard someone whistle, and the bullets started flying like a son of a gun. The other guard with the good gun was hit, and I never saw him again.

The Russians had broken through our front line, so our officers yelled to retreat. A Panzer II tank was in a ditch, and a bunch of us went over to help pull it out. Russians were all along the road, maybe 100 meters from us when we got the tank out. We all jumped on, and I crouched on the metal guard plate for the track.

I couldn’t carry the machine gun and hold on at the same time, so I gave the gun to another guy. The Russians were throwing everything at us. Artillery shells were exploding all around, puffs of black smoke and debris flying everywhere. Soldiers in front of us would get hit, but the tanks just kept going, moving forward right over the fallen bodies. That is when I said to myself, “If I get through this alive, I never die.”

Right then the tank driver said something to me about how white the guy behind me was. I turned and saw that he had been hit and was trying to hold on. I grabbed him by the hand to keep him from falling. All of a sudden 30 meters behind me there was a red flame and black smoke. Shrapnel from the exploding shell tore into my face, ripping off my upper lip and knocking out four of my teeth.

I didn’t even realize I had been hit. I must have been in shock; I just jumped down and started running.

We had the white sides of our coats turned out for winter fighting, and when I looked down, the front of mine was red from all the blood pouring down my face. My mouth felt like it was full of gravel, and I spit out shrapnel and teeth.

Somehow I made it back to the first aid place, and they bandaged me. At 7 that night I was put in a Mercedes truck and taken to the Park Saloda Hotel on the Pest side of Budapest where a makeshift hospital had been set up in the basement.

Castle Hill, originally built in the 13th Century, was across the Danube on the Buda side of the city, and I was moved there later the same night.

Sometime after midnight they took me up to an operating room to chop off a section of my lip and sew everything together. That was the only time I ever saw a doctor, and I never was given anything for the pain; no anesthetic, no pain medication, no nothing. One tooth was broken and the others had been knocked out by the artillery blast.

I suppose I was lucky to be alive; if the shrapnel had hit the side of my head, I would have been killed for sure. But all I remember is the terrible pain. The blood caked under the bandage and the little bit of whiskers I had at 18 grew into the mass of blood and scabs.

After one week a first aid guy came in to give me a new bandage. He just grabbed the old one and pulled it away with no warning at all. I tell you, the pain was unbelievable.

When everything ripped away, I wanted to kill that guy. After that I moved my bandages a little each day so nothing would stick like that again.

While at Castle Hill I discovered a storage room where equipment and supplies were kept. Some clothing was also in there, and I noticed a new pair of leather boots that I took for myself. They were a little tight on me but beautiful, the kind that lace up the lower part of the leg.

Surrounded

By the end of January 1945, most of the troops had retreated into Castle Hill. Four or five stories high and with thick walls, it could be defended against the bombs and shells the Russians threw at us. There were ports in the walls where machine guns could fire out, and there were tunnels where many wounded were kept.

The most severely wounded, those who could not walk even with crutches or a cane, were down in the lower tunnels. I could walk and get around quite easily, so my job was to carry water to the kitchen.

As the Russians slowly surrounded the city, conditions inside Castle Hill got very bad. If there was any food at all, it was weak soup and maybe some very bad bread that I’m sure had sawdust in it. Out in the streets the shelling sometimes killed a horse, and when that would happen, people would cut something off the dead horse to eat. But even the horses were skin and bones and didn’t provide much to anyone.

Food or supplies that were dropped to us either fell into the river or were grabbed by the Russians. It was the middle of winter, the weather was just terrible, and we were slowly starving.

Sometime in early February I found my older brother Joe. After volunteering he had fought the Russians all the way to Moscow, but he was at Castle Hill the same time I was in early 1945. One night when outside I heard some of our soldiers talking loudly and I said to myself, “I know that voice.” I yelled to him, and I’ll be a son of a gun, it was Joe.

Surrender

Things grew worse, and by February 11, everyone knew the situation was hopeless. The officers told us we could try to break out and get through the Russian lines back to Germany, or we could surrender. Almost 30,000 troops tried to breakout, and fewer than 1000 actually survived. Most were killed by the Russians in and around Budapest, as were many thousands of Hungarian civilians.

On February 13, 1945, my brother Joe and I were among roughly 5000 troops, many of them wounded, who surrendered to the Russians. That was the day I became a prisoner of war. I was only 18, and I would not be a free man again for nearly nine years.

The Russians told the wounded who could walk with crutches or a cane that they could leave, they could try to walk back to their home countries. Those too sick, too weak, or wounded and unable to walk were left down in the tunnels on beds of straw. The rest of us were judged healthy enough to become slave labor for the Russian conquerors.

A Terrible Story

I have to tell you what I heard about those wounded men left down in the tunnels. I heard this from a woman who was a civilian in Budapest. Some time after the war she married a Hungarian man who had been a prisoner with me.

After the surrender there was so much murder and terrible raping in Budapest by the Russian soldiers. This woman was a teenager at the time, and like many other young women, she wore several layers of clothing to make herself look older, heavier and unattractive, trying to keep from being raped. She was not raped, but she was forced by the Russians to do cleanup work.

The lice were so terrible in Castle Hill. The straw bedding in the tunnels looked like it was crawling, there were so many lice. Apparently the Russians gave the wounded soldiers left behind gasoline to rub on themselves to kill the lice.

Well everybody smoked. Soldiers smoked and prisoners; everybody. It must have been the gasoline the very weak ones rubbed on themselves, and it must have been someone smoking that started the fire. Shortly after the surrender, about 2,000 of those prisoners were burned alive when a fire tore through the catacombs. My friend’s wife was one of the women forced to go into the tunnels, and many years later she told me about having to drag out the charred bodies.

Bakonysarkany is west of Budapest; Tiszalok, to the east.

POW

The first day after our capture, we were forced to walk to Budakeszi, about seven or eight miles outside Budapest. We marched again on the second day, and there was this place where all these Jews were gathered, kind of like a picnic area. The Russians put them there and made all of us prisoners look at them as we marched by.

Germany had occupied Budapest in March of 1944, and in November that year, the Jewish quarter was made into a ghetto, and about 200,000 Jews were kept there behind a high fence and stone wall. In January, after about three months, the ghetto was liberated, and I’m sure the Jews we saw that second day were from the Budapest ghetto.

That night we stayed in a wine cellar, and my feet were killing me. The leather boots I took at Castle Hill had gotten wet, and my feet swelled inside them from all the walking. I couldn’t take them off.

The next day I took two vineyard stakes to use as canes to help hobble along. We were put into lines based on how healthy we were. I got into a line, and behind me there were four or five guys who were worse off than me, limping along as best they could.

Suddenly I heard a shot. This guy who had been at the end of the line was on the ground, and the Russian guard was putting his gun back over his shoulder. Then he went to the next guy at the back of the line and shot him! They were shooting the ones they thought were too weak to keep walking.

My brother was next to me, and he said, “If they think you can’t walk, they’ll shoot you. You must keep up.” So I dropped the vineyard stakes. Let me tell you I had tears in my eyes, it hurt so much to walk, but I was afraid they would shoot me. As I walked my feet felt a little better, and I could shuffle with less pain. I kept moving farther up in line, away from the back.

The guard ended up shooting all the guys who had been behind me when I first got in that line.

That night we stayed in a school, and in the evening a Russian guard decided he wanted my boots. He started pulling on them and shouting something in Russian. Those leather boots had not been off since our capture, and my feet were still swollen inside. He pulled even harder, and then he took out his pistol and pointed it at my head.

Even though it was in Russian, I’ll never forget for the rest of my life what he said. “Ya streilite, ya streilite,” meaning “I shoot you, I shoot you.” I begged him, “No, No, No.” I didn’t know Russian, but I pushed on the boot as hard as I could, and finally the first one came off. Then he pointed the pistol at my head again and started pulling on the second boot. It too finally came off. My feet were swollen and the pain was terrible, but he didn’t shoot me. He took those leather boots and gave me the ones he was wearing, boots made in America with rubber soles.

I think it was about the third or fourth day after our capture when the Russians forced us to strip our clothes off so all the hair on our bodies could be shaved to get rid of the lice. Our clothes were put into a room and made very hot, so hot the buttons burned our skin when we put them back on. But the heat had killed the lice.

On the fifth day we were loaded onto a Studebaker truck the Americans had supplied to the Russians, and we were taken to Temeschwar in Romania.

Temeschwar: “We Lived Like a Shoe Nail”

We were kept about two months in Temeschwar, those of us who survived. I had been raised on a farm, and I was young and tough. But the Russians had grabbed everybody in Budapest; old men, young men. Civilians. People who had been raised in cities. We lived like a shoe nail in Temeschwar, and many of those who were not tough would die there.

When we arrived my brother and I were separated. He had shrapnel pieces in his back from an earlier wound and was taken somewhere to be treated. I would not see him again until many years later.

In this camp at Temeschwar they had five buildings, each divided in two. They put 800 men in one building, 400 in each half, and the living conditions were unbelievable. We had no room; 400 people in a space like my kitchen and half my living room today. Standing in there we were right next to each other. To lie down, we had to be in rows with our knees bent, all facing the same direction. If we straightened our legs, we kicked the head of the guy in the row below us. To turn over, the whole row had to turn over. And if someone had to go to the toilet, nothing but cursing and yelling. Unbelievable. And always full. If someone died, they brought in another guy. Always 400.

The toilet was outside, a hole dug in the ground with a log over it to sit on. If it rained, the hole filled up and everything ran down a ditch next to the barracks. I can’t doctor this up to make it sound better; it was really like that.

My barrack had a wood floor, but the other four buildings just had dirt. For food we had a little cabbage soup—water, some salt, and maybe a leaf of cabbage. My barrack got that lousy soup at 2 a.m. each day. At 11 in the morning, we got a little cube of bread. Nothing more.

That wasn’t enough to live on, and some of the weak ones died each day. A horse wagon came by, and we dragged the dead ones out to be picked up. Next to my barrack was where they put the dead; sometimes 100, sometimes 110 a day. One morning I woke up and told the guy next to me to wake up too. But he was dead.

No Food, No Water, No Nothing

Toward the end of April, 1945, about two months after arriving at Temeschwar, we were loaded into railcars on a small gauge railroad. We began a five-day trip I never will forget in my life. No food, no water, no nothing for five days. About 60 or 70 men in a boxcar. Four vertical layers of board platforms to lie on, a guy right next to you and a board shelf with more guys right above you.

There was a little semicircle space in front of the door where a guy could stand. The doors remained open about six inches. A board maybe one inch by six inches came down from the ceiling and a piece was nailed across the opening in the doors. That was the toilet. When you used it, everything went flying out the opening in the doors.

After five days on this little railroad, we finally arrived in Ploesti, Romania about 3 in the afternoon. We were dying of thirst, but they wouldn’t let us out right away. After half an hour, I got up and moved over by the doors.

Right then we heard a shot and a buddy—the guy who was sitting next to the spot I just left—fell over. A Russian guard outside the boxcar had been fooling around with a gun and discharged it. The bullet went through the boxcar wall and killed my buddy. If I had still been sitting there, it would have killed me instead.

Finally they let us out, and we all cried, “Where’s the water, where’s the water?” We saw some water running in a trough on the ground and fell down on our hands and knees and began to drink it. It was greasy, soapy water, coming from an area where men had been washing, and I remember thinking to myself, “I can’t believe I’m drinking this bad water.” But we were all so thirsty we didn’t care.

To Siberia

We were only one night in Ploesti. The day after we arrived, the Russians loaded us onto large gauge railroad cars, and we began a 34-day journey to Siberia. The cars were very much like the ones we had traveled in from Temeschwar; the same layers of board platforms to lie on and the same type of toilet. No blankets, no mattresses. We had only the clothes we wore when captured at Castle Hill, and we used our boots for pillows.

Food was cooked in a kitchen car, and when we stopped, terrible beet soup and maybe some type of corn would be brought to the individual cars where we were kept. There were always Russians with guns guarding us when the food came to the cars.

It was during one of these stops sometime in May when a Russian guard kept saying, “Jvar Kaput,” trying to let us know the war was over, Germany had surrendered. But there was no celebration in the railroad car. The war was far from over for those of us on the train.

Sverdlovsk

That train carrying about 2,000 prisoners continued east and north, crossing the Ural Mountains and reaching Sverdlovsk on the 34th day.

Although some would continue on, I was among about 250 Hungarian prisoners ordered off at Sverdlovsk. There I saw many German prisoners who had been captured at Stalingrad earlier in the war.

The weather was so unpredictable in Siberia during the summer. The first night at Sverdlovsk we had a foot of snow, and the next day it was warm. All the snow disappeared just like that. If you thought it was hot one morning and did not take your coat out to work, the clouds could come over and make it so cold you thought you’d freeze.

I worked in different places at Sverdlovsk during the three months I was kept there. For a time I worked in a factory that made ammunition for rocket launchers mounted on trucks. I did some construction work, and I also worked in the forest harvesting logs that were loaded on old T-34 tanks that had the gun turrets removed.

To this day I remember the bedbugs at that camp. The walls were crawling with them at night. They were terrible; if you slept and they began biting you, you didn’t feel them. If a light went on, they disappeared. And these were fat bedbugs, full of our blood. We never had enough to eat, but I tell you, the bedbugs never went hungry.

Life in Siberia

At most of the camps in Siberia, we were given enough clothing to try to keep out the worst of the winter cold, but we never seemed to have enough.

The coldest I experienced was 68 degrees below zero, but anytime it was colder than 30 below, we didn’t have to go outside to work.

Frostbite was always a risk. I remember a guy who was given a job unloading loaves of bread from a wagon to the kitchen, and he did the job with no gloves. When he was done, all his fingers were frostbitten, and he ended up losing them.

We wore many layers of heavy pants and sweaters and jackets. The fabric on our shoes was an inch thick, and we wrapped this wool thing around our heads and faces so only our eyes were exposed. You never knew who anybody was until they talked. Even then we had little ice things on our eye lashes.

I tell you, if somebody pushed you over, you had a heck of a time getting up. And to take a leak? Oh, that was a disaster!

We slept in barracks in Siberia that were buried in the ground far enough so the little windows were just above ground level. Usually there were about 250 in one barrack, and you would sleep right next to someone to stay warm.

The ground insulated the buildings, and there was a stove inside for some heat. Everybody who went out working brought a piece of wood or coal back to the barrack at the end of the day. Some crippled guys who couldn’t work would stay up at night to load the fire.

Once in two or three weeks, we would get a shower. They would take us to a room and we would take all the clothes off and get into a shower that wasn’t hot, but it was warm enough to be comfortable.

In some camps they gave you a canteen type of thing as well as a spoon, but sometimes a spoon was the only possession you could have. Mine was a steel thing…the handle was a knife and the other side a spoon. So if I ever got something like a potato, I could cut it and then chew with the side of my mouth that still had teeth. A prisoner always kept his spoon with him.

Most of the food we were given was very plain. If there had been a good corn crop, we had some type of corn every day; corn for breakfast, corn for lunch and corn for dinner. If wheat had been good, we had some kind of wheat for every meal. The same thing with beans. Never meat, only a mush type of thing—just grain, salt, and water. The only vegetable was stinging nettle, and you know, once it is cooked, it is perfect. It doesn’t even taste bad.

I remember two times when we had something more. Once the guards had been given some beef, and when they were done, they gave us the bones, and let me tell you, we sucked those bones until there was nothing left. Another time, they got in barrels of salmon and gave us some pieces. We ate every bit, including the bones.

Nizhnv Tagil

Russia had been beaten down in many ways during the war and needed laborers to help rebuild it. There were labor camps every 10 miles or so in Siberia, and not only POWs but also Russian political prisoners and criminals were sent to these camps.

Whenever I was moved, I was always sent north. After spending June, July, and August at Sverdlovsk, I was loaded on a train and sent north to Nizhny Tagil, a large camp of nearly 3,000 workers, a place where I would spend the next three years.

We were grouped by nationality at Nizhny Tagil, and one of my first jobs was to help build a sewer line with picks and shovels. The line had to be buried over two meters deep because the ground was often frozen to that depth in winter.

Stalin was fearful that he could find himself in a war with America, so he was still building weapons. At Nizhny Tagil, we had a factory that made more T-34 tanks. Many of us also unloaded coal for the steel smelting factories. Iron ore was mined nearby, and although mainly Russians worked the iron, prisoners at times were given the job of loading the slag onto little railroad cars so it could be hauled away.

My Tattoo

One day at Nizhny Tagil the KGB came, and all the prisoners were made to take their shirts off and raise their hands over their heads. During the war when the Russians had examined the bodies of dead Waffen SS, they had learned about the A or the B or the O blood type tattoo the soldiers had been given. Now they were looking to see which of their prisoners had been Waffen SS.

And wouldn’t you know, the KGB sent home many of the prisoners who did not have the tattoo. Stalin figured that the SS guys must be Germans, and he wanted to keep them and have them work more years to punish them for the war. The non-SS Hungarians were sent back home sometime in 1948, but they told me and guys like me we were German and had to stay.

One day at Nizhny Tagil the KGB came, and all the prisoners were made to take their shirts off and raise their hands over their heads. During the war when the Russians had examined the bodies of dead Waffen SS, they had learned about the A or the B or the O blood type tattoo the soldiers had been given. Now they were looking to see which of their prisoners had been Waffen SS.

And wouldn’t you know, the KGB sent home many of the prisoners who did not have the tattoo. Stalin figured that the SS guys must be Germans, and he wanted to keep them and have them work more years to punish them for the war. The non-SS Hungarians were sent back home sometime in 1948, but they told me and guys like me we were German and had to stay.

Now listen to this. It is a story my brother told me long after the war. Like me, he had a blood-type tattoo on his left arm. And although he was in a different camp, he too was told to strip to the waist and raise his arms over his head.

But my brother always had big ear lobes; he raised his arms quickly and his ear lobe covered the tattoo. He put his arms down just as quickly, and no one saw his tattoo. He was sent home in 1948, and once back in Hungary, which had become a communist country, he was able to escape across the closed border into West Germany.

Starving

The years 1946 to 1948 were very bad in Russia. There were shortages of everything, and what there was, Stalin tried to stockpile in case the cold war escalated. So it was a very bad time for citizens, but it was even worse for prisoners.

From October of 1946 to January of 1948 nobody in the camp was really working. The guards didn’t make us work because they knew we had no energy. We were starving. Of 3000 prisoners, maybe 100 might go out for three or four hours a day to bring in

any supplies that might be available to keep us alive.

During this period, I got down to 45 kilos, under 100 pounds. Sometimes if I had to climb a couple of steps, everything would go black for a few seconds because I was so weak from hunger.

Of course as a prisoner there were times when I would think of holidays or home, think of girls or what my family might be doing. But during the time we were starving, we only thought of food. We didn’t think of home or freedom or family. We thought of food and nothing else. Only food.

And we would look for food whenever we could. Of course searching for it backfired on me and other prisoners more than once. One time when we were outside, a German prisoner found some mushrooms. He heated the blade of a shovel and fried the mushrooms right on it. Well, I thought I wanted some of those, and I went looking for mushrooms so I could do the same thing. I found some, heated them the same way, and ate them right up. Oh boy. An hour later I had the worst stomach pains, and my eyesight went all crazy. They sent me to the camp doctor in a little barrack where they did some medical work.

In that place, they stuck a tube down my throat and pumped water into my stomach. Oh, it was terrible. Other guys had to hold me down, and I gagged and gagged. But all that stuff came up. Then they stuck a tube in the other end and washed me out that way too. Oh man. They gave me no food for four days. But I guess it saved me from those bad mushrooms. I’m still here.

Sometimes we would look around in the garbage from the guards’ quarters. I knew a guy who found some old coffee grounds and ate them. But he got so sick that he landed in the medical barrack.

The Russians would doctor some of their stuff so prisoners wouldn’t try to eat it. I remember one time a guy came across a barrel with some kind of oil in it. When he stuck his finger in and tasted it, he thought it tasted a little like sunflower seed oil, so he took some back to the barrack and later put it on a crust of bread. After that he had nothing but diarrhea for three or four days. The Russians had put something in the oil, I’m sure.

Early in 1948 the ruble was devalued and new money was printed. Things improved at Nizhny Tagil; they fed us more and we could work again. And again we started thinking of things other than food.

First-Class Liars

Sometimes I’m asked how I could put up with forced labor for so long, and the answer is that we always had hope. We always hoped we’d go home. And the Russian mentality to keep prisoners from giving up hope was to promise us something three months in the future. Actually, to lie about the future.

They would say, “We will send some of you home in three months.” But in three months they’d have an excuse…“The bridges washed out” or “We have a new job to do first,” or “You didn’t get enough work done.” Russians are first class liars.

One fellow Hungarian I remember saying to me in 1948, “If I knew they would keep me here this long, I would have killed myself.”

Krosna Ural

Toward the end of 1948, after three years at Nizhny Tagil, I was moved north again, this time to a camp called Krosna Ural, or in English, Red Ural. The place was about the size of Modesto and had perhaps 1,000 prisoners altogether. The Russians thought they were keeping the guiltiest ones there. At Krosna Ural, there was another sorting of prisoners, and the Germans who had been Wehrmacht, or regular army, were allowed to go home. I was kept.

Here I worked mostly in a huge copper mine. There was an elevator that went down 300 meters into the earth, and side tunnels led away from the main shaft in many directions. We were made to drill holes in the rock with a compression drill that used bits two meters long. We would drill nine holes, and then a Russian lady would come in and wire explosives into the holes. We would move around the corner, and then the charge would send stuff flying like a son of a gun.

We shoveled the ore into little mining cars, pushed the cars over to the main shaft and dumped them. When a large cart at the bottom of the shaft was full, it was hauled to the surface.

Word from Home

Until this time, my family assumed I was dead. Letters out of Siberia were censored, which really meant they never got out, especially if you mentioned you were starving. But while at Krosnal Ural in 1949, I received the only letter I would get during the time I was imprisoned.

You see, there was a Hungarian guy in camp with me who had heart problems and who was told he would be sent home. He was from a little town where a neighbor woman from my home village had moved. When I was young, my family had helped this woman, kind of looked out for her. I asked the guy who was headed home to tell this woman I was alive. And he did.

I did not know at the time that my mother and sister had moved to England, but this woman in Hungary did, and she wrote to my mother. My mother wrote to my aunt in Canada and sent her my brother’s new address in Stuttgart, West Germany. It was my aunt who wrote to me from Canada.

I never knew if my mother or sister wrote to me. If they did, the letters never arrived; the Russians probably threw the letters in the garbage. My aunt’s letter was the only one I received, and in it, she passed on my brother’s address. It was a street number I would memorize and never forget.

The Next Camp: Karpinsk

In 1949, they moved us farther north, to the end of the railroad line and a camp at Karpinsk. There I found the biggest coal mine I ever saw in my life. At Nizhny Tagil I had unloaded coal that had come from this place.

In Karpinsk, there was about four meters of topsoil above 75 meters of solid coal. Topsoil would be scraped away, then holes would be drilled all the way through the coal.

When the charge was set off, the coal would slump to the bottom of a huge pit where a conveyor belt brought it to the surface. Giant backhoes would fill railroad cars in just three scoops. The equipment we used was often American, given to the Russians by their Allies at the end of the war.

Often I worked moving railroad tracks. They were just lying on top of the ground and were very flimsy, not secure at all. We moved the tracks often, and I always was afraid the locomotives would fall off.

The town of Karpinsk was pretty new at the time, and there was not much there. Streets were just mud, and there were no sidewalks in the town. Some of the work we did was to build the main road and side streets.

We used slag from the iron smelting at Nizhny Tagil for road base, loading that on Mercedes trucks the Russians had captured from the Germans during the war. The Russians—especially the truck drivers—were very happy with us for the paving we did.

Leaving Siberia

After 10 months at Karpinsk I left Siberia, but I was not set free. In 1950, many of us were put on a train and sent down through Moscow to the Russian town of Woronesh. The town had been totally bombed out during the war and was still in ruins.

We were expected to work on the reconstruction there but were never asked what we could or couldn’t do. They might say, “Today we need 50 men to do carpentry,” and 50 of us would have to go.

There were two main camps in Woronesh, and I was in the second. I actually lived in a hammer factory, and we had metal bunk beds with sawdust or woodchip mattresses.

By then it had been more than five years since the war had ended, and by December of 1950, we were fed up and didn’t work very hard. There were days when most of the time we just leaned on our shovels. If someone told us to get to work, we did it for a couple minutes and then stopped. It was kind of like a labor slowdown.

It must have worked because Stalin said we were more trouble than we were worth, and he decided to get rid of us by finally sending us back to Hungary, a country that was by then under communist rule.

Not Happy to be Home

The train to Hungary arrived in a town called Nyiregyhaza in the middle of the night, and right away we could tell it wouldn’t be a happy homecoming. At the train station we were met by dogs, high beam lights, and soldiers with machine guns. The AVH, or Hungarian secret police, interrogated us all night and then transferred us to jails in Budapest.

It was prison all over again. They put about 150 in one room with only straw on the floor, and although we had a sink and a toilet, for the first four or five days we were only allowed to drink water. We were given no food.

A little short guy, an officer, would come in and play with our minds. He might tell us how lucky we were, that we were going to be given all the bacon we could eat and allowed to write letters home. Five minutes later he would return and tell us we were guilty of great crimes and that we were going to be taken out, shot, and our bodies thrown in the Danube because nobody knew we were there.

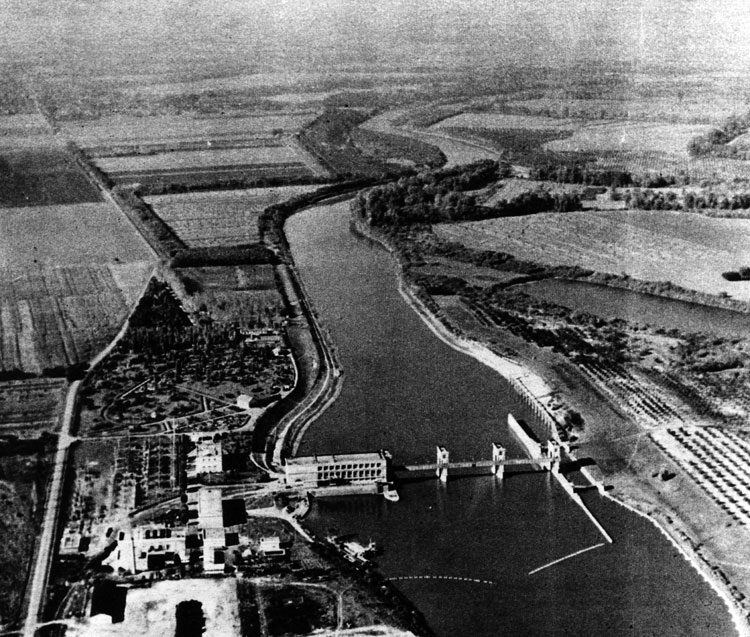

Hydroelectric plant at Tiszalok

Tiszalok

I had been a prisoner of war in Siberia for almost five years, and now back in my home country, I would be a prisoner of war for three more. We were held in the jail in Budapest for a month, and then in January of 1951, the Hungarian government sent me to a newly built forced labor camp next to the Tisza River. It was Tiszalok.

Hungarians prisoners who said they wanted to go to the west were sent to Tiszalok, a total perhaps of 2,000 men. The Hungarian government was building a hydroelectric plant on the river, but to generate electricity, the flow of water through the turbines would have to be increased. To do that, the course of the river would have to be altered.

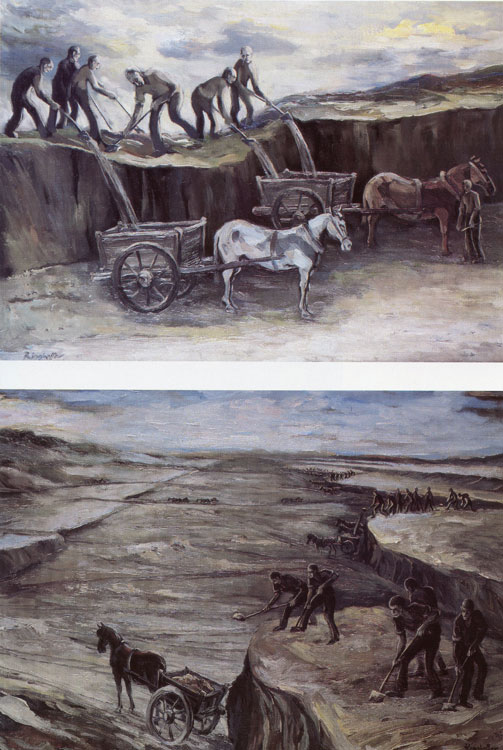

We were told to take the bend out of the river where it approached the site of the plant. Using picks and shovels and horse-drawn carts, we were to dig a new channel, straightening the river and making it drop in elevation to increase the current. We would dig two kilometers, then a drop, then one kilometer more. All by hand.

At first, oh my God, they thought they were going to really give it to us bad. They fed us only this turnip soup that gave everyone diarrhea, and we became too weak to work. It was like Siberia again. The guards realized that plan didn’t work, so they started giving us soybeans and we did better, we could work again. I thought to myself during this time, “I’m Hungarian, but I’m in a Hungarian prison doing slave labor. This shouldn’t happen.” But the guards would tell us they could take our citizenship from us because we had fought for the Germans. They would tell us they could shoot us any time, and no one would know.

The first year at Tiszalok my main job was to lead the horses that pulled the carts of dirt prisoners had filled. After that they taught me to weld, and I started working in the shop or in the hydroelectric plant as it was being built.

I have to tell you about a young Hungarian officer who was a prisoner with us then. He told us his name was Lazlo John, and he claimed he had fought with the Germans, but nobody remembered him from any prison camp in Russia. When we asked him which POW camps he had been in, he claimed he couldn’t remember. Finally we found out he was planted there, a turncoat, a spy. There was another man I should mention also. He was one of the

Paintings by Tiszalok prisoner Josef Ringhoffer of inmates creating new channel for Tisza River; images used by author’s permission

guards, an officer, and because he was so tall, we called him “The Long One.” This was a guard that all the prisoners respected. He would listen to us, and in turn we would listen to him.

Beatings

Prison in Hungary was worse than Siberia in many ways. I never got beaten, but over half the inmates were badly beaten while at Tiszalok. We called one of the guards “The Boxer” because he always punched prisoners in the face. If he called someone out for interrogation, they came back from there with a tooth missing or a bloody nose or a bloody face. He was “The Boxer,” but really he was a butcher. A Hungarian who hit other Hungarians.

The uncertainty made it so hard; you never knew what was going to happen. There was a time when we were digging the new river bed. Guys shoveled dirt down to a cart, and when it was full, it was pulled out by a horse and emptied. One day this prisoner asked another, “Why do you work so hard? We don’t get nothing for this.”

That spy, the one who said he was Lazlo John, heard those guys talking. Later, the one who had asked the question was called out. They beat him so hard, and then he had to stand on the wall—nose on the wall and knees on the wall all night. If you don’t stand on the wall you get beaten with a rubber stick. They did this to the guy for two weeks. When he came back to us he could hardly talk. Only a whisper. He made it out of prison eventually, but I remember him saying “If I ever get back here I’m going to kill so many of them.” He hated the communists so bad.

For punishment they sometimes would make a prisoner bend over, then handcuff his wrists crossed to the opposite ankle and beat him. If he fell over, they beat him. If he passed out, they poured water on him and beat him some more.

We had so many regulations: Take off your hat in front of an officer; never go anywhere alone or as a group of three, always two guys together. If you were alone or in a group of three, they beat you. I always followed the regulations, and that is why I didn’t get beaten. I was young and I always looked even younger than I was; maybe that too was part of the reason I wasn’t beaten.

Josef Ringhoffer, a very good artist, was an inmate at Tiszalok while I was there. In 1993 he published a book of paintings that record the work and the misery and the desperation that consumed each prisoner at the camp.

Messages Out

We worked through 1951 and 1952 and 1953, always wondering if people in the west knew what was happening to us. We wanted to get word out somehow, and we found a way.

The horses that were used to haul the carts of dirt belonged to civilians who lived nearby. Each morning they came in with the horses and took them back each night. These farmers probably got paid something for the use of their horses.

Well, we got to know a farmer, and he hated the Hungarian communists. We asked him if he would take a little note and try to pass it along. We wrote down how many people were in the camp and where they came from. We folded the note and pushed it under the blinders on the horse.

Notes like that, smuggled out of camps like ours, slowly made their way to West Germany, and a push began to release prisoners like those of us at Tiszalok. But we didn’t know that was happening.

The Uprising

By the autumn of 1953, after nearly three years of labor at Tiszalok, we got to the point where we could care less about life and the future. We were thinking, “Kill us, do whatever. We’re not going to work any more. All you do is lie to us. We’re tired of it.”

On October 4, 1953, the guards called a meeting in the afternoon. The big boss wanted to give us a pep talk to increase production and finish the project. They always referred to us by our numbers rather than by our names. At the meeting, we were told we could talk, we could voice our concerns, but before talking we had to give our number. Some guys went up, gave their numbers, and talked about all the lies; “You said we could go home, but then we didn’t. You said we could write letters, but then we couldn’t. All lies.”

Later that afternoon, the guys who had stood up and talked were called out and taken away. Maybe 10 guys.

The Long One, the only guard we trusted, was not in camp, having been called to Budapest a few days earlier. If he had been there, we probably would have gone to him.

That evening out in the yard, we all started yelling, “Give us our comrades back!” It got louder and then even louder, everyone yelling like mad.

The prisoners saw Lazlo John in the crowd and thought that was finally the time to get him. They started beating the hell out of him, but somehow he escaped and slid under the fence. But the guys in the guard towers knew he was really one of them and didn’t shoot him.

The yelling continued and after awhile, the little short officer, the one who promised us bacon way back in the Budapest jail and then told us he could shoot us, came in the yard to try to quiet us down.

I had been up toward the front with all the young guys, but about then I realized I had better think about what was going on. A Hungarian countryman of mine, Joe Meyer, was about 10 years older than me and was a guy I always trusted. Before the war, his family had lived about six farms over from mine. I said to myself, “I better find Joe and see what he is doing.”

I moved back toward the doorway to Barrack #2 where he was standing and said, “Joe, what is going on?”

He said, “Come over here and watch out. They’re going to start shooting.”

Just then the prisoners started for the little officer, and the bullets started flying.

The officer had taken out his gun, and the guards in the towers had started firing theirs down into the crowd of prisoners. When it was over, five prisoners had been killed and 30 more were wounded.

Memorial in Tiszalok, Hungary to five killed in Oct. 4, 1953 uprising

Today, there is a memorial outside the hydroelectric plant that explains what happened and lists the names of the five who died that night.

Leaving Tiszalok

The uprising could have been avoided, I’m certain, if The Long One had not been away in Budapest. And it should have been avoided because steps toward freeing prisoners like me were already being taken.

Reports of what was happening in camps like Tiszalok had reached the west, and Hungary was being pressured to release us. The Long One had been called to Budapest to discuss just how that would happen.

Immediately after the uprising, the guards punished us by giving us only water to drink. No food.

But on the third day, The Long One returned and visited each of the barracks. Then we were made to go outside, to stand in a line, and facing us were Hungarian soldiers carrying machine guns. We thought, “Oh boy, what is going to happen to us now?”

Then The Long One said, “What do you guys want to eat? You’re going home.”

Right away we got better food. And for the next two months, more good food and no work. Then in December 1953, about two months short of nine years since I had been captured, I was put on a passenger train that headed west.

There were just over 100 men in each car, and we only had the clothes that were on our backs, but when we passed Budapest and kept going, we started to relax. There was still much of Hungary on the other side of the Danube, and they could always turn around. But they didn’t. They kept heading west.

When we reached the Austrian border, I finally allowed myself to think, maybe I really am going to be free. I had been given a Hungarian passport when we left Tiszalok, and at the border, a French delegation counted us by name and nationality and placed us in Austrian train cars.

When that train stopped at a station inside Austria, we saw nurses standing there holding hands. When I think of it today, I still get very emotional. We could get out and walk around, walk wherever we wanted to. There were tables of food and chairs to sit in. I tell you, I never in my life had a sausage or a bun that tasted so good. Never in all my life.

Finding My Family

At that station, we were loaded onto buses and taken to Piding on the Austrian-German border. Two days there gave us a chance to clean up. I threw away my prison clothes and got new ones from a place like the Salvation Army here.

We each had to send telegrams. I had my brother’s address in Stuttgart still memorized and sent a telegram there. It didn’t go through. I sent it again. Back came an answer from a woman who said she lived across the hall from my brother’s place, but he was no longer there.

In the telegram she told me my brother had emigrated to Toronto, Canada and that my mother and sister had also moved there from England. But she didn’t have the address.

In Piding we were given train passes to go wherever we wanted. When they saw me with my face wounds and when I gave my brother’s old address, the people in Piding told me I should go to Stuttgart. There were hospitals there where my wounds could be fixed.

Success

In Stuttgart we were given passes to go anywhere we wanted on streetcars, and I immediately tried to find my brother’s old address in the Feuerbach section of the city. I told a conductor where I wanted to go, and he took me right to the building.

I pushed the first button. Nothing. I pushed the second button. Nothing. The third button. Suddenly a window opened up above me, and a fat lady called out, “Yaa?”

I asked if Joe Klesitz used to live there, and again she said, “Yaa.” It must have been the same woman who answered my telegram from Piding. I told her I had lived in POW camps, and she buzzed me up. I talked for quite some time, telling her my story, and she cried, she was so sorry for me.

I left briefly to get food, and when I returned, my brother’s friend who lived with the woman was there. He knew the address of the aunt and uncle of the girl my brother Joe had married. It was two kilometers away, and he said we should walk over there right then. So we did.

My sister-in-law’s aunt and uncle were home, and they gave me the address in Canada for my family. When I got home that night to the little mission where I was staying, I thought, “Man oh man, am I lucky. And won’t my family be surprised to learn I am alive.”

Five Operations

I told the officials in Stuttgart I was going to Canada in six months, so I had to have my face fixed right away. The skin had healed well in the nine years since I was wounded, but everything had kind of grown together.

During the next six months, I had five operations. They took cartilage from my ear and rebuilt part of my nose, and they took skin from my thigh and used it on my mouth where the inside of my lip had grown into the gum.

The dentist was authorized to give me silver teeth to replace the missing ones, but he said, “No, you went through so much, I’m going to put gold ones in.” And he did. For many years my front teeth were gold.

At the hospital they made noses for guys, they made lips, they made jawbones. They saved so many war veterans however they could. I tell you, I was a movie star compared to some of the wounded ones there.

Steve in Stuttgart, 1954

During my six months in Stuttgart, I lived either at the hospital or with the aunt of my brother’s wife. The German government supported me with streetcar tickets, and they gave me some money, which I gave mostly to the aunt.

Lisa

After the fifth operation, I did some physical therapy each day for about two or three weeks. There was a young nurse, about 18 years old, who had just started working at the hospital. I would talk a little to her each time I went in for treatment.

When I went for my last appointment, I had my papers for Canada and was ready to leave Germany. I went around and said goodbye to everyone. When I said goodbye to that young girl, she said, “I hope I hear from you.”

“I don’t know your name,” I said. She told me then it was Lisa.

I Thought I was in Heaven

I got on a train in Stuttgart, traveled to Bremerhaven on the coast, and boarded a ship, ready to leave behind both Germany and the life I had known.

I was leaving not only a country but a continent that had been ravaged by war. I had seen so much pain and starvation and people being mean to each other. Stuttgart had been bombed out during the war, and even in 1954 the damage was obvious.

On June 11 that year, I arrived in Canada and thought I was in heaven. Within two days

I was reunited with my family in Toronto. Oh man, it was exciting. So many questions. They wanted to know everything that had happened to me. Questions and more questions.

My mother at the time was working as a live-in housekeeper for a family there, so I moved in with my sister, Regina.

I remember I first saw my brother on a Saturday, and he asked me what I could do. I told him I could drive a car, and I could weld. He said, “In that case you’re going to be a body man.”

On Monday, just two days later, we called around, and on Tuesday I went to work in a small auto body shop owned by a Norwegian who paid me 70 cents an hour and who began to teach me that trade.

I learned very fast, and when he ran out of work in three months, I worked for another guy for a dollar an hour. Not only was I learning how to use lead to fix dents—no one used bondo then—but I was also learning English. Back in one of the camps in Siberia, there had been a prisoner who was very good with languages, and he had learned English. He taught me a little, but of course it does not stick until you start to use it.

Lisa, age 20

Lisa Again

The second Christmas I was in Toronto, I bought some cards to send to my friends. I had just one left and thought to myself, who should I send this last card? I hadn’t even thought of Lisa, the young nurse who had treated me in Stuttgart, but I remembered right then she had told me when I left she hoped to hear from me.

So I sent her that last card and asked her if she were interested in coming to Canada. She wrote back and said, “Yes, I’m interested.”

We started writing back and forth. I think she was 20 and I was about 29 by then. I found out that to come to Canada she would have to go to immigration and tell them she was engaged. And once in Canada, she would have about 90 or 120 days to get married.

Well, I remembered what a nice girl she was, and I thought I might marry her…she was very good looking. So I told her all of this, and she decided to come.

Lisa arrived in June or July, 1956, and we were married in Toronto on October 20. Our son Ron was born there in 1957.

I continued to learn the auto body business and worked for a number of different shops and dealerships, but Toronto was cold, and I often thought of finding a warmer place to live.

In 1962 this guy I knew left for a long vacation to America, planning to drive around the whole country. By then Lisa had an uncle living in Redwood City, and I asked this guy Martin to check out the weather for me in the Bay Area. When he returned to Canada, he told me the weather was perfect, that you could wear just a shirt in the evening all year. Well that is what I wanted.

California

In 1963, Lisa, Ron and I moved to Redwood City, and within a few days I had a job doing bodywork at Smythe Buick when it was still in San Jose. I commuted for about 10 months before moving the family to Campbell.

Our daughter Janet was born in 1964, Anita in 1967, and my second son, Eric, was born in 1969.

Smythe Buick moved to Santa Clara in 1965, and I continued to work there until I started my own business in 1968. That year there was a strike of the auto body union, and during the strike, a guy I knew, a Porsche mechanic who had worked at Lockheed, talked to me about going into business. He had a building that was much too big for him and invited me to use half of it to start an auto body shop. So I did.

I retired 13 years later, and I have to say a lot happened in those 13 years. We had plenty of money, but money doesn’t make people happy, and Lisa wasn’t happy. We separated two different times, the second and last time in 1978. She stayed in the house in Campbell, and I moved to Morgan Hill.

After our divorce, a Swedish friend talked to me about investing in natural gas wells in Oklahoma, and I began to do that. That was also about the time I met Marie Lapierre through the German Club down there, and we began dating.

America is the land of opportunity. I worked hard, my business was very successful, and the gas wells turned out to be a good investment. Those are the reasons I could retire in 1981.

Lisa died on the 3rd of July in 1984. She was baking some things that day and while walking to the market to buy sugar, she was hit and killed by a young man driving with just a learning permit.

Steve waterskiing at New Melones Reservoir

Sonora

Though I kept the property in Morgan Hill, I bought a house in Sonora in 1987 and moved here that year. In 2004 I became a U.S. Citizen, and in 2005 I exchanged the Morgan Hill property for 140 acres overlooking Melones Reservoir, where I live today.

My children are all grown, and I have six grandchildren and one great-grandchild. Marie moved to Sonora too and is still my girlfriend, 35 years after I met her.

These days I stay busy, taking care of my place and doing things with the local German Club. I water ski in the summers, and I snow ski for three months during the winter. Since retiring I’ve been able to travel to places like Australia and New Zealand, and I’ve been through the Panama Canal.

Back in 2000 I took my son Eric to Tiszalok to show him the hydroelectric plant and the memorial to those shot in the 1953 uprising.

Steve Klesitz, 2012

Reflections

I wasn’t proud to be in the Waffen SS. Unlike those who volunteered, I was drafted and went where I was ordered. I tried to shoot the enemy because I knew if I didn’t, they would shoot me. It wasn’t whether or not you liked what you were doing. You didn’t want to get killed.

By 1944 we knew they were rounding up the Jews, but we didn’t know where they were sending them. I found out about the death camps in 1953 when I got home.

Many times I’ve been asked if I am angry or depressed about what happened to me. People wonder if I have nightmares, or if I am somehow bitter that I lost so much of my life to being a prisoner of war. And when people hear my story they wonder how guys like me got through it all.

I’m not angry or depressed. I sometimes have a dream about that time, but when I wake up I laugh and say, “Oh, I’m so happy that I’m here and not there.”

I learned some good lessons during that time, too. Many officers who had been businessmen before the war were prisoners with me, and I often talked to them, asking them what they did and how they got started. I think that helped me later.

And believe it or not, when I was in the camps, I tried not to dwell on it. If you did, it could kill you. It would just eat you up.

I think that attitude carried over into my life after the war. When I would leave my body shop each night, I shut the door and didn’t think about it until the next morning. When I got home at night, I couldn’t even tell you what cars were in the shop or what I had done that day.

It’s true, some very bad things happened in my life. But some very good things happened too, just like in anybody’s life. And I tell you, if it hadn’t been for those very bad things, the best thing in my life would never have happened.

You see, in 1963 we wanted to leave Canada and come to the United States to live. But there was no way they were going to let me in. After the Hungarian revolution in 1956 and the flood of refugees from it—some of them released criminals—countries didn’t want more Hungarians.

I argued and explained to the authorities that German was my first language, that my home village was German-speaking. I told them about being drafted and my wounds, about being in the prison camps.

Finally they said, “Your wife is German. Okay, we’ll put you in the German quota for immigration.”

You see? If I hadn’t been drafted, I wouldn’t have been wounded. If I hadn’t spent nine years in those terrible prison camps, I wouldn’t have been having my wounds fixed in a German hospital in 1954, where I met Lisa.

And if I hadn’t married Lisa, I never would have made it to the United States.

And coming to America was the best thing that ever happened to me.